Should it impact when you sell your property?

Every election cycle, the same question resurfaces across New Zealand’s property market: Should I wait until after the election to sell?

It’s a narrative that gains traction in headlines and at open homes alike - the idea that elections bring hesitation, uncertainty and a pause in activity. Buyers sit on their hands, and vendors hold off listings, with the market “waiting to see what happens.”

But does the data actually support that view?

Recent analysis prepared by Bayleys suggests the answer is more nuanced than many assume.

A MIXED HISTORICAL PICTURE

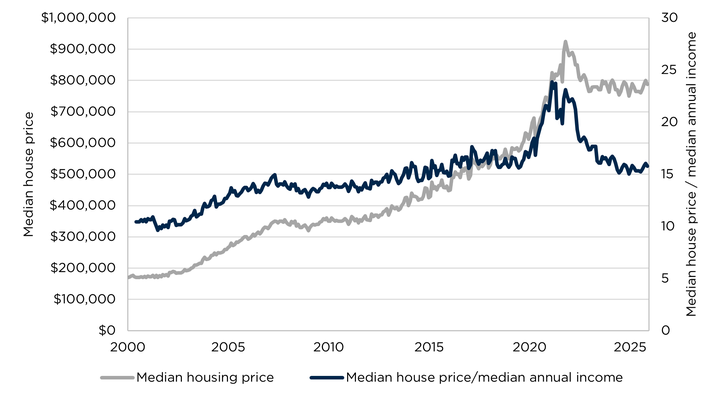

Looking back over multiple election cycles reveals no consistent pattern showing a definitive “election slowdown.” While election years often coincide with market shifts, the drivers are rarely political in isolation. Bayleys Senior Analyst Eos Li says the data tells a complex story.

“When comparing the two quarters before and during each election year (relative to the prior and subsequent years), the results show mixed movements.”

“Some indicators rose, some fell, and others remained flat. This makes it difficult to attribute short-term housing market movements directly to election timing alone.”

In other words, elections don't automatically mean a decline in activity. In some years activity held firm. In others, it softened, but often for reasons unrelated to politics and instead linked to broader economic forces such as credit conditions, global events, or affordability pressures.

Li says based on that, the housing market, it seems, tends to follow fundamentals more closely than political cycles.

A TRIP DOWN MEMORY LANE

Looking back to the early 2000s, Li says there’s little evidence of any meaningful election effect at all. “Market conditions during those cycles appeared to track broader economic fundamentals rather than political calendars.”

Sales volumes did take a dive during the 2008 election period, but she says context here is critical. “It was actually the Global Financial Crisis that drove a significant economic and housing downturn.”

“Ultimately, market forces overwhelmingly overpowered any election policy effects. The slowdown was global and financial in nature and not election-driven.”

Li says the GFC was a structural economic shock and the election happened to fall within that period, but it wasn’t the catalyst.

The 2014 and 2017 election cycles also showed weaker activity. Li says the impact in 2014 is less clear, but the year before the 2017 election marked the previous market peak. Affordability had become stretched, lending conditions were tightening, and momentum was already easing.

“This marked a natural turning point and dip in activity. Affordability concerns had intensified, and housing-specific policies began to exert more noticeable influence on market sentiment and behaviour.”

She says with activity already coming off a high base, any election-related uncertainty was amplified, not created.

In contrast, the 2020 election period recorded significantly higher sales volumes.

“Pandemic-driven stimulus and historically low interest rates boosted the market significantly. Macro settings far outweighed policy discussions.”

Ultra-low interest rates, relaxed lending settings and unprecedented fiscal stimulus drove demand, overriding political uncertainty entirely.

During the last election in 2023, sales remained relatively the same.

SO WHAT REALLY DRIVES THE HOUSING MARKET?

Li says across all cycles, one theme stands out.

“Macro-economic conditions, particularly interest rates and credit availability, remain the primary drivers of housing performance.”

“Interest rates influence borrowing power. Lending policy shapes accessibility. Employment confidence underpins buyer appetite. These fundamentals consistently outweigh election-specific policy debate.”

Even when examining buyer psychology around election periods, Li says the data suggests the housing market remains tied to larger economic forces.

“Unless there are significant macro shocks, such as a financial crisis, sharp interest rate movements, or major external disruptions, the housing market is likely to continue responding primarily to broader economic conditions rather than election-specific policy settings.”

That doesn’t mean sentiment doesn’t shift, but Li says sentiment alone rarely overrides economic fundamentals.

IS “ELECTION HESITATION” REAL?

Li says it’s often assumed both buyers and sellers retreat during election periods.

“Some vendors may perceive increased caution. Some buyers may delay decisions if major policy changes are proposed, such as discussions around capital gains tax, but the overall data does not show a consistent nationwide freeze.”

In reality, Li says that hesitation tends to be selective and short-lived. It may affect certain segments, particularly if policy proposals directly impact taxation or investment property rules.

“But across the wider market, activity continues, albeit sometimes with slightly longer decision-making timelines.”

Li believes the idea of an “election slowdown” persists largely because elections bring heightened media attention and amplified uncertainty.

“When examining each election cycle within its broader macro-economic context, clearer patterns emerge.” “The headlines may focus on politics, but the housing market tends to follow money, and the cost of it.”

WHAT SHOULD VENDORS EXPECT THIS ELECTION?

Li says the housing market is likely to continue responding primarily to broader economic conditions rather than election-specific policy settings during the campaign period.

However, there are practical considerations this year. Proposed tax changes - including renewed discussion around a capital gains tax may influence some investor behaviour, interest rates may begin to rise later in the year, and credit conditions could shift.

“Based on long-term data, elections appear more likely to create short-term sentiment shifts rather than structural turning points unless accompanied by something more significant.”

“That includes things like a financial crisis, sharp interest rate movements, or major external disruptions.” For buyers sitting on the sidelines due to election nerves, the risk of waiting too long could mean exposure to changing interest rate environments or tighter lending conditions.

And for vendors, delay may not necessarily reduce risk, it may simply change it.

KEY TAKEAWAY FOR VENDORS

For vendors, the message is clear: timing decisions should be anchored in economic fundamentals rather than political headlines.

“While we will continue to monitor conditions as the election approaches, history suggests that waiting purely because of the election calendar may not be supported by long-term data.”

“Bringing property to market earlier, particularly ahead of potential tax reform discussions and possible interest rate movements, may provide greater certainty.”

Ultimately, Li says the question shouldn’t be: “Is it an election year?” It should be, “What are interest rates doing? What is credit availability like? And what is happening in your specific local market right now?”

Because while elections may influence sentiment, history suggests it’s the fundamentals that move the market.